5 Lessons on the Road To Clinical Changemakers

My journey to the first podcast guest

With the launch of my first episode tomorrow, I found myself reflecting on how I got here.

Now usually I don’t spend any time looking back on my career. But once I did, I found a few experiences that connected my journey to my first guest’s area of expertise.

Lesson 1

When it comes to ideas, commitment is key.

I felt like an imposter for most of medical school. The kind where you think you’re only one slip-up away from being identified as a fraud. My grades were fine, but I was sure getting through each year was just some sort of sinister deferral process until my ultimate undoing. It wasn’t until my final year (2012) that it dawned on me. There will be no escape from discovery once I graduate.

With this self-doubt, I found solace in strategising with my classmates. Like good med-students, they had already sought to curb this concern, by throwing time and textbooks at the problem.

Through this, they’d begun creating a condensed resource of pragmatic clinical guidance called “The House Officers Bible.” It contained practical tips like, what coloured blood tubes are used for which tests, a short listing of common antinausea medications, and which intravenous fluids to use for which circumstance.

I saw this as a way to couch some of my concerns and joined up to contribute.

Our goal was a single, searchable document, that would be stored on all desktop computers in the wards.

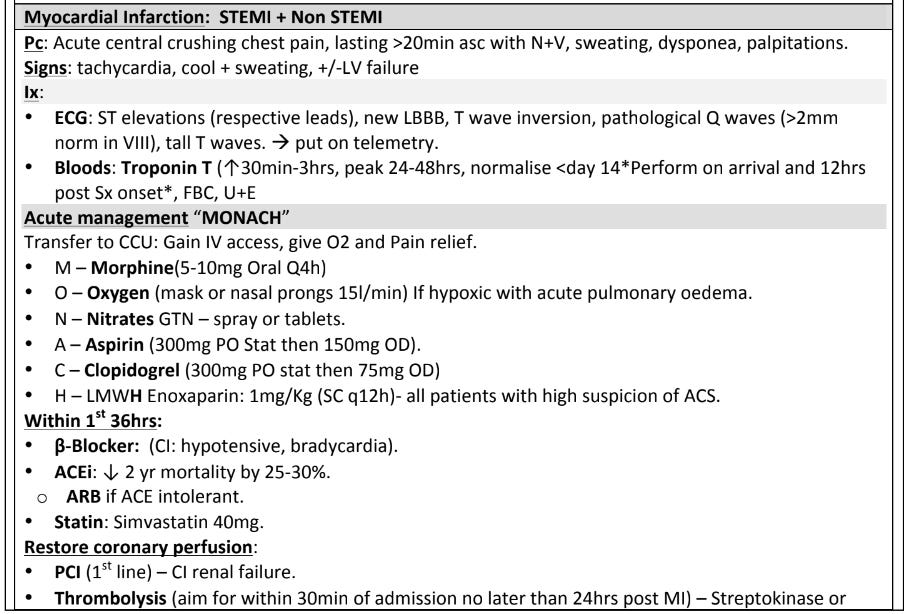

An example of the management of a heart attack from the ‘HOB’.

Lesson 2

You don’t know until you go to the frontline.

Landing on the wards a short time after, the reality of working as a House Officer (Intern in the US) changed my thinking. Rather than being some perfect clinical expert (which was my main concern), I needed to be a clinically-minded administrative conductor.

This meant being a facilitator and coordinator for the support of senior clinicians and patient needs.

An example before a General Surgical Round:

Arrive before the team, check if anyone new was admitted overnight, check which rooms they were in, record any new blood results or scans, review any on-call or overnight assessments, have the right paper for requesting scans or blood, write down the patient’s inputs/outputs, check against any discharge criteria, follow up with allied health…

As you can see, many tasks for a new doctor are clinically orientated but with an operational lean. Adding to this complexity are other senior doctors’ preferences, regular rotations, different IT, and new hospitals - and now these quirks get magnified.

A picture of a pager (beeper) from the wards.

This front-line experience helped me to reframe the kinds of problems junior doctors faced. Strangely while I had shadowed doctors as a student, it wasn’t until my responsibility and accountability had escalated, that I had clarity on the day-to-day challenges of MDs.

So rather than create clinical guidelines, what if I found a way to just surface the clinical and administrative information? With access to that information, I could turn my attention to real medicine.

(I say real medicine, but administrative tasks are real medicine! Without it some of the most important things would never get done).

Lesson 3

Understand the Human Interests.

After a few months, I decided to ask my Consultant (Attending in the US), why this problem wasn’t solved already. Her reply was simple but effective, “I don’t know, why don’t you do something about it.”

Note, in the hospital hierarchy, if a consultant ‘suggested’ you do something, it means you do it. So after talking to a few other junior doctors around the hospital, I was encouraged to ‘get funding’ for this idea.

That sounded easy enough.

I found an organisation chart in some orientation documents and identified someone in the finance team to approach. My grand idea was to wait for them after a meeting to ask for funding to develop an online resource to help junior doctors.

In the doorway, his reply was, “How many surgeries am I going to have to cancel to pay for this?”

I think my jaw touched the ground when he said that. I had no response. I hadn’t considered the response to be no or that there was something to weigh it against. It was a good idea and it would help, right? A mix of my naivete and hubris on full display.

Lesson 4

A Leader’s Words matter.

Needless to say, I felt pretty deflated by that response. Clearly there was nothing I could do, so I reported back to my Consultant - I’d done my best after all.

Her response was, “Okay Jono, so what are you going to do about it?”

Another sage piece of reorientation.

Hmm, rather than learn how to put together a business case, I thought I’d try just going straight to the source to see if it could be done for free. I then went on an expedition to visit our hospital’s IT team. (FYI they are usually hidden in the hardest-to-find part of the hospital). There, I was kindly greeted by a team who were surprised to see a doctor visit them in person. I was equally surprised they were happy to help for free.

Over the next few months, I put together a detailed mock-up, designed functionality, gathered guidelines and links, tested and troubleshooted bugs, and then managed feedback requests from other junior doctors.

A picture of the website. (RMO stands for registered medical officer).

Today this probably seems easy and obvious, but a decade ago it did not exist.

On reflection, my Consultant’s subtle words of encouragement, perhaps not even particularly considered, set me off on the path of thinking about improving healthcare in a different way from what I had been taught.

Lesson 5

Opportunities breed opportunities.

The success of this website opened up a whole new range of opportunities, leading to an invitation to present to the hospital leadership team on building a Quality Improvement (QI) program within our institution.

Little did I know that a few years later, I would have the privilege of interviewing Dr. Kedar Mate, the President and CEO of the renowned Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), a global leader in quality improvement.

Listen on Substack, Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.